I think the problem is that games with deep strategy are timeless, no real need for a new release.

“Another potential hypothesis is that the increasing negativity, polarization, intrusiveness, and emotional manipulation in social media has created a persistent cognitive overload on the finite cognitive resources we have,” Quantic Foundry said. “Put simply, we may be too worn out by social media to think deeply about things.”

in other words, we’re burnt out and we just want some escapism …

Not sure if this is true. Social media shows a very distorted view on polarization. Past research shows that the vast majority of polarising content (>95%) is generated by a vast minority of users (~6%). It is shown repeatedly that the polarization found in (online) media, differs drastically from every day felt polarization.

Literally “getting off the internet” seems like a valid strategy. I think it is more likely that .odern games hijack native reward systems more than “deep strategy games” do (whatever that means). In fact the gameplay mechanics in most games are still relatively the same, just prettier, faster running. Back in the day we couldn’t have a high FPS shooter with a lot of bang simple because the technology didn’t allow for it. Furthermore games were a niche back then as well. Now games are more mainstream and the relative group is smaller, than the mainstream group.

That’s too bad. Lotta good thinking games.

Meanwhile I have 3000+ hours in Civ6…

Someone who isn’t into strategy games will play shallow strategy games like fire emblem because its anime and allows you to date anime girls with big boobs.

I love 4x games, but playing a game of Stellaris for a week or more just to realize that I’ve inescapably fucked up and lost the game is disheartening. I just don’t have the bandwidth to spend 40 hours per match. Yeah, you can make 4x games run a lot shorter, but it usually feels like you’re doing something crazy to the game.

But across its 1.7 million surveys, Quantic Foundry found that two thirds of strategy fans worldwide (except China, where gamers “have a very different gaming motivation profile”) have lost interest in this element of video games.

So what’s the story with China?

goes looking for the original

https://quanticfoundry.com/2018/11/27/gamers-china-us/#post/0

The Quantic Foundry (QF) data comes (as usual) from the Gamer Motivation Profile, a 5-minute survey that allows gamers to get a personalized report of their gaming motivations, and see how they compare with other gamers. Over 350,000 gamers worldwide have taken this survey. The survey is in English and thus respondents are predominantly from North America and the Western EU.

The Niko Partners (NP) data comes from an online survey (in Simplified Chinese) of 2,000 representative digital gamers in China (from a survey panel provider), balanced across more than 40 cities in tiers 1 through 5.

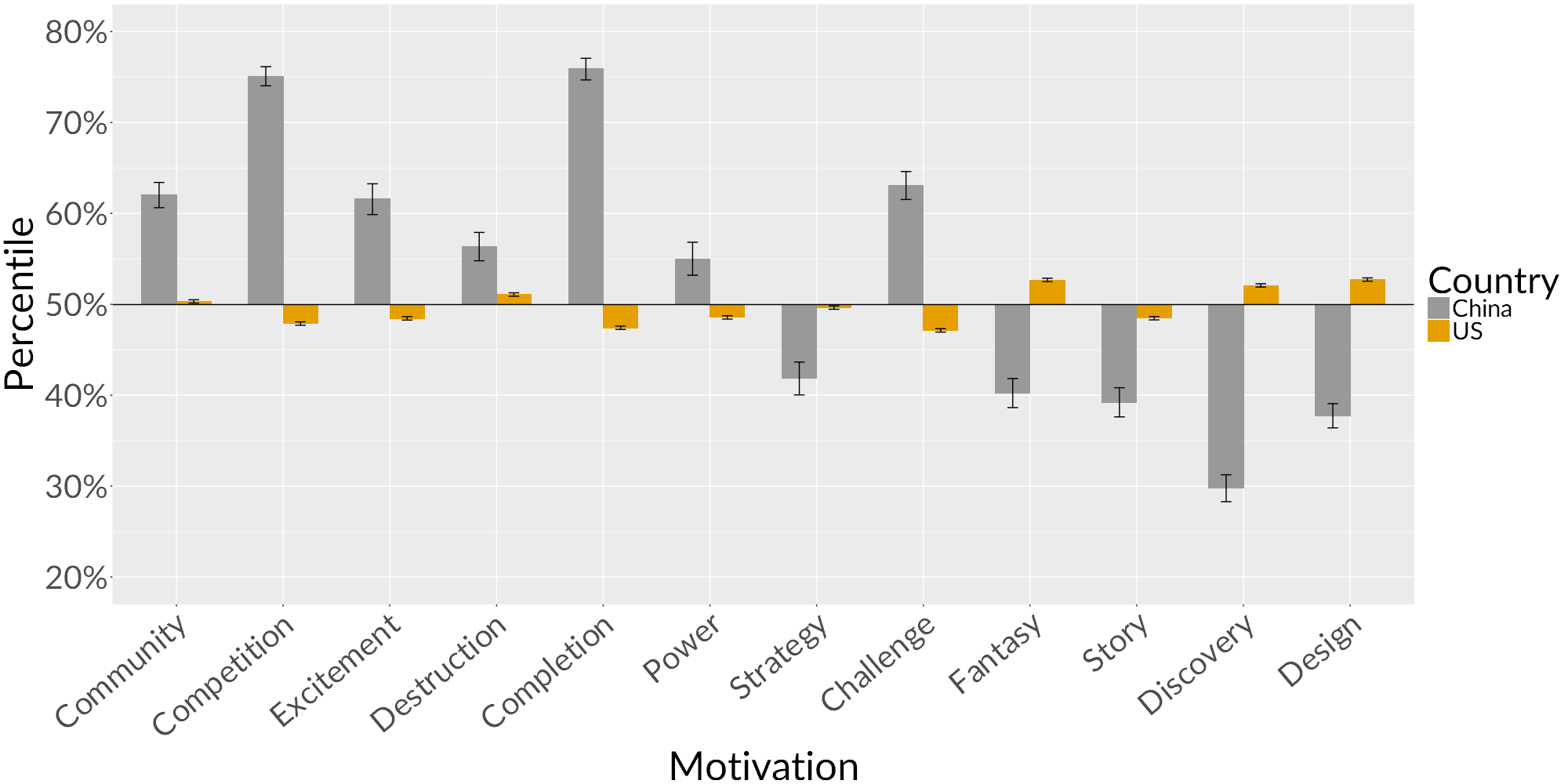

The Gamer Motivation Profile is benchmarked against QF’s existing data set (based largely on gamers in the West). In the chart below, the 50th%-tile line indicates the perfect average of each motivation in QF’s full data set. This is why the US data (a large portion of QF’s data set) hews closely to the average. The error bars in the chart are based on 95% confidence intervals.

https://i0.wp.com/quanticfoundry.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/01-US-vs-China.png?ssl=1

Let’s take the 75th%-tile that Chinese gamers score on Competition—the appeal of duels, arena matches, and leaderboard rankings. That 75th%-tile means that the average Chinese gamer is more interested in Competition than 75% of gamers in QF’s data. Given that the US data is so close to the average, this also essentially means that the average Chinese gamer cares more about Competition than 75% of US gamers.

Similarly, Chinese gamers are also more interested in Completion—the appeal of collecting points/stars/trophies, completing quests/achievements/tasks. Conversely, Chinese gamers score below average across the Immersion and Creativity motivations (the last 4 motivations in the chart). They are less interested in being immersed in a compelling game world (Fantasy), interacting with an elaborate story and large cast of NPCs (Story), exploration and experimentation (Discovery), and customizing their avatar/town/spaceship (Design) relative to US gamers.

The Competition finding may seem unintuitive because in the US cultural context, we tend to stereotype Asians as being compliant and striving for social harmony. But the data strongly suggests this stereotype doesn’t hold true among Chinese gamers, and the higher interest in Competition can help to partly explain the popularity of games like PUBG in China. After all, Battle Royale is probably the furthest away you can be from “social harmony”.

In previous blog posts (see here and here), we’ve shown how male gamers (in the West) tend to be more driven by Competition, Destruction, and Challenge, whereas female games tend to be more driven by Design, Fantasy, and Completion.

The data from China looks very different. Of the 12 motivations, only 3 cross the threshold for statistical significance (at p < .01)—male gamers in China care more about Destruction, Discovery, and Competition. Of these 3, the differences in Competition and Discovery are substantively small (about 5 percentile points apart). Overall, the only robust difference is that female gamers in China are less interested in guns, explosions, and mayhem than male gamers. In contrast, 9 of the motivations are at least 10 percentile points apart in the US data between male and female gamers.

In the US, there’s a lot of contention around the cause of observed gender proportions in different game titles and genres, specifically as to whether these differences reflect the historical marketing/cultural framing of games for boys or deeply-rooted biological differences between men and women. The data from China suggests that even very large gender differences in gaming motivations can be almost entirely explained by cultural/marketing factors without using gender as an explanatory factor.

Age Differences Are Also Much Smaller in China

In data we’ve previously shared using QF’s full data set, we’ve shown that the appeal of Competition declines dramatically with age, and it’s the motivation that changes the most with age. The appeal of Excitement also declines a lot with age in the US. The table below presents the correlation coefficients between age and each of the 12 motivations, broken down by country.

In China, the age differences are much smaller (similar to what we saw with gender differences). None of the correlations in the China data exceeds 0.10 (what is considered a small effect in psychology research), and only 4 of the coefficients are significant at p < .01. In contrast, 7 of the coefficients exceed 0.10 in the US data, with 2 coefficients exceeding 0.25.

So while the appeal of Competition and Excitement drop rapidly among US gamers as they get older, these effects are much more muted among Chinese gamers.

Motivation Homogeneity and Making Games

When gaming motivations vary a great deal in terms of gender and age (as they do in the US), it means game design and marketing have greater difficulty in being broadly appealing to different gamers, because they will often run into breakpoints in terms of gendered or age-based appeal.

On the other hand, the homogeneity of gaming motivations among Chinese gamers suggests a higher likelihood of cross-cutting appeal of game titles. Put another way, a game designer for the Chinese market likely has to worry less about satisfying orthogonal or opposing interests among different players because most Chinese gamers tend to care about the same things (high Completion and Competition, low Discovery).

Huh.

So, first of all, regarding the Strategy thing that the derived article was talking about, it’s not that Chinese gamers prefer Strategy more. Rather, they prefer it less. But they haven’t seen that decline, and they have both different and much more homogenous preferences.

But the other stuff is curious too.

Strategizing feels dangerously close to work for me.